We know that when faced with a drawer full of junk it can be very difficult to throw away things we have no regular use for. A study at Yale School of Medicine has been able to track the brain function that we go through when faced with such decisions as keep or throw, save or toss. The school invited a mixed group of hoarders and non-hoarders to meet with them for research and asked the group to sort through items such as old newspapers and junk mail. The test was structured to include items that belonged to the researcher and other items belonging to the participant. Those taking part had to decide on what to keep and what to discard and while they were doing this the research team tracked the brain activity of those sifting through the items.

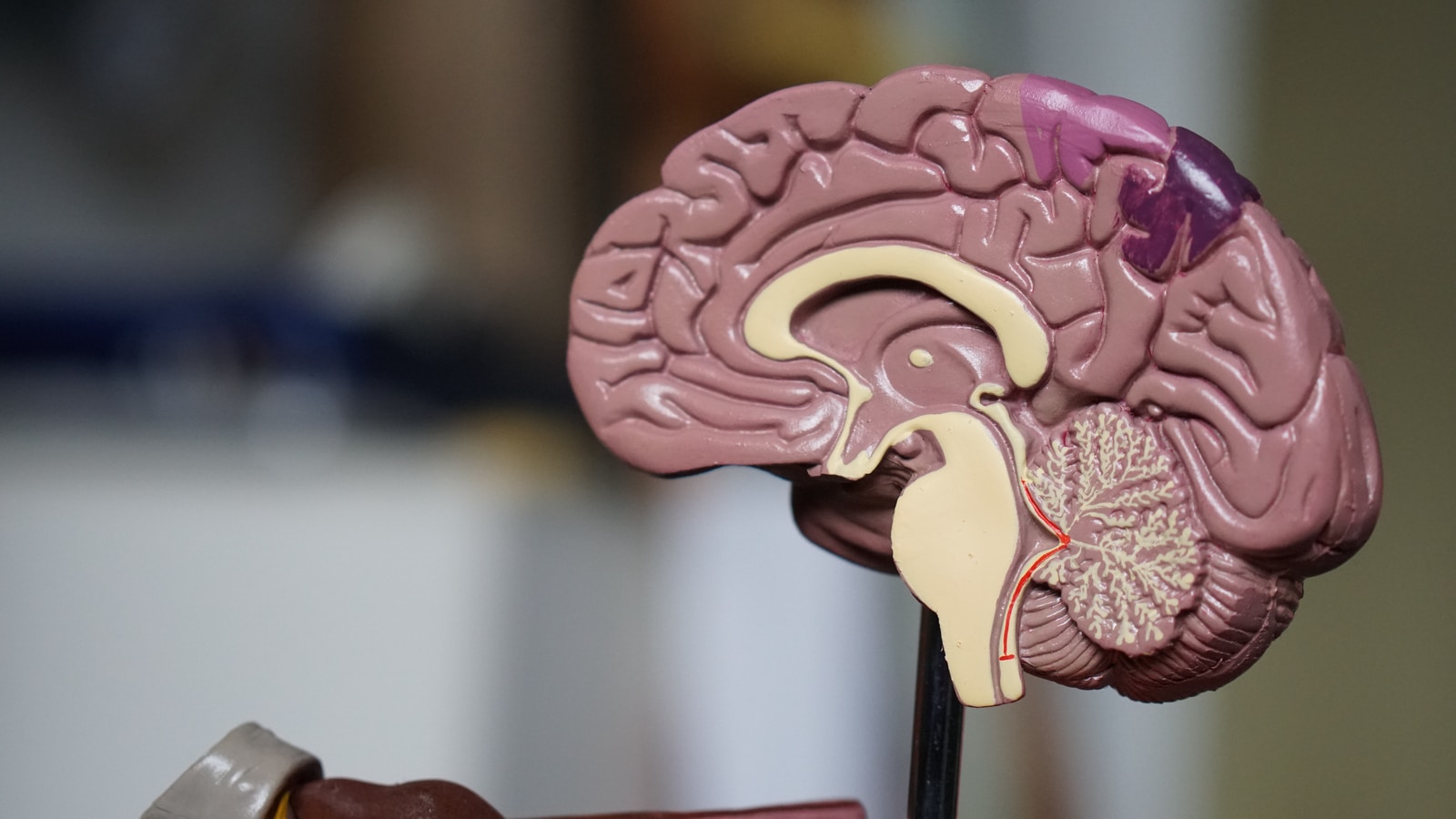

When faced with how to deal with their own stuff that had been included in the observed test, the hoarders had increased activity in two areas of the brain, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the insula. The greater the struggle that the hoarder felt about whether to throw something out, the more this pattern of brain activation was recorded. The activation of the trigger between the ACC and insula sections of our brain is creating a message that there is 'something wrong' and we need to defend ourselves against the doubt or uncertainty. Keep the item and the unease reduces. These two areas of the brain are moved into play when a smoker wants to give up tobacco or an addict approaches the decision to quite the drug they use. Keep the cigarette and the fear of loss weakens. The greater the activation of the two parts of the brain, the more we feel discomfort, unease and anxiety and so we reach again for the cigarette.

Compulsive shoppers also recognise the same brain activity when faced with a high price on an item. They can put lesser priced items in their trolley all day long if this feeling makes them restful and happy while they accumulate, but when faced with a high priced item, the brain message allows them to push the item away and move to something where the brain has no threat-response activation. This process can be an explanation of why there is a strong self-sustaining element involved in the behaviour of the hoarder. When we find and decide to hold onto an item, we feel calmer and all is good with our world.

Do you struggle to throw out books, or clothes or beer bottles from different breweries? If you like reading, dressing yourself a certain way or have a nostalgia for drinking games from college days, then let's see what the link might be. Other research into hoarder behaviour has shown activation of another area of the brain, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (or vmPFC). The more this is activated the greater the feeling we have of wanting something. It is often the case that the item we are attracted to reinforces our sense of "Me" or of "This is who I am". If you have a tendency to hoard and to accumulate it might be that you are seeing those books sitting on shelves or stacked on your stairs as a reflection of who you think you are, or those wardrobes jammed with clothes as who you are when walking out in the world, or of those old beer bottles with different labels as reflecting back to you how much fun you had with your drinking games. Recognising how the vmPFC element of your brain is activated by the books or bottles, which others see just as junk or mess, can help you understand that you no longer need all this to be who you are.

You may have hoarding disorder if :

You struggle to let go go items because you think they should be saved and where you get distressed over the idea of letting them go.

The volume of things piled high, stacked, and placed within your home space makes it difficult for you to move about freely.

You buy things or always accept free things that you don't need and for which you don't have space anyway.

You have difficulty discarding, donating, recycling or otherwise gifting things that other people would be unlikely to keep in their house after use.

This can lead to a lot of belongings stashed at home and cluttering up walk ways through the home, presenting an obstacle course that is also like to become a fire hazard. It is likely to lead to strain and conflict within the family, but also can lead to isolation and loneliness due to the fact that others - potential partners - will not understand the problem when they see it and want to avoid living with it, or because the hoarder knows that the behaviour is potentially a block to social activity and the embarrassment of inviting people home to discover the accumulation of possessions.

As well as the behavioural difficulties in discarding, of constantly saving items, packaging and clutter, many compulsive hoarders have the difficulties which come from disorganisation, indecision and perfectionism bordering on OCD. Such traits can make their private lives difficult as well as impacting on their social lives where they rarely allow people into their home space for fear of ridicule, shame or guilt at their inability to manage the possessions they have gathered together in the one space.